Introduction

I’ve been spending some time outside of work messing around with writing Linux kernel exploits and analyzing Linux kernel vulnerabilities. This was my first time touching Linux kernel exploitation since reading A Guide to Kernel Exploitation: Attacking the Core and writing some basic kernel exploits almost ten years ago. From my perspective, the space has both changed significantly since then, while in many ways also remaining relatively unchanged. There are of course new mitigation technologies and there are elements that make exploitation more difficult than before, but the basic concepts used and many of the bug classes remain very similar.

To begin my research, I decided to take a look at CVE-2023-0266 after reading an excellent article written by Seth Jenkins from Google Project Zero titled Analyzing a Modern In-the-Wild Android Exploit. The article discusses an exploit chain used against a Samsung phone running Android which leverages a combination of n-days and zero-day vulnerabilities within the exploit chain. From my perspective, the most interesting aspect of the article is the number of vulnerabilities exploited by the attacker which had been patched within upstream dependencies, but hadn’t been backported to the targeted device. The attacker leveraged some very interesting kernel exploitation techniques within the article as well using a combination of vulnerabilities in the Linux kernel and the Mali GPU driver in order to exploit the vulnerability.

After reading through the article, I thought it would be neat to deep-dive a bit more into CVE-2023-0266 to better understand what common vulnerability patterns look like within the Linux kernel. The article from Project Zero provided a ton of useful technical details, but it didn’t provide a super-detailed analysis of the vulnerability. I thought it would be fun to write up a quick article describing the vulnerability in a little more-depth in an easy to explain manner.

Understanding the Vulnerability

As Seth documented in this post, the root cause of the vulnerability arises from there being a compatibility layer used for compatibility with 32-bit applications running on 64-bit systems. This compatibility layer means that there are different versions of the IOCTL available for 32-bit and 64-bit userland applications. One of the IOCTLs exposed to user-mode applications allows users to add sound control elements to a sound card and user’s can read and write to the sound control elements once they are added.

Unfortunately, while the 64-bit version of the IOCTLs implement proper locking, the 32-bit versions of the IOCTLs don’t properly check the lock when reading and writing to elements. This introduces a race condition vulnerability where the attacker can attempt to remove a sound control element while simultaneously trying to read or write to the sound control element.

The worst case scenario here would be the attacker is able trigger a use-after-free via a race condition where the write operation reads an attacker-controlled sound control element object. The sound control element fields such as function pointers and other fields which can be used to either gain control of program execution or trigger an arbitrary read or write.

To exploit the vulnerability the attacker needs the following actions to be performed:

- The attacker should trigger the removal of a sound control element while triggering a read or write of the sound control element (for the rest of this example we assume the attacker is triggering a write operation to avoid repeatedly saying both read and write).

- Sound control elements are stored in a linked list that is referenced for performing look-ups. To exploit the issue we need to trigger a free of the sound control element while at the same-time it is being read and used by the vulnerable IOCTL handlers.

- The attacker needs to reclaim this memory before it is used by the vulnerable IOCTL handlers so that they can control the member fields of the sound control element structure.

- If the attacker successfully reclaims the freed object’s memory space before it is used the attacker can gain control of the instruction programmer or trigger an arbitrary read or write within the kernel.

Often when writing these types of exploits the key is to understand the primitives provided by the vulnerability and then leverage exploitation techniques that allow you to leverage those primitives to achieve a desired outcome (e.g. root access on a server or the ability to break out of a Linux namespace).

Digging into the Linux Sound Subsystem

The root cause of this vulnerability is related to there being multiple ways to trigger IOCTLs through an exposed management interface for sound control management. There’s a 32-bit version and a 64-bit version of the IOCTL handlers, but when the code got updated, they accidentally removed the locking on the 32-bit handlers.

How do we access or invoke this functionality?

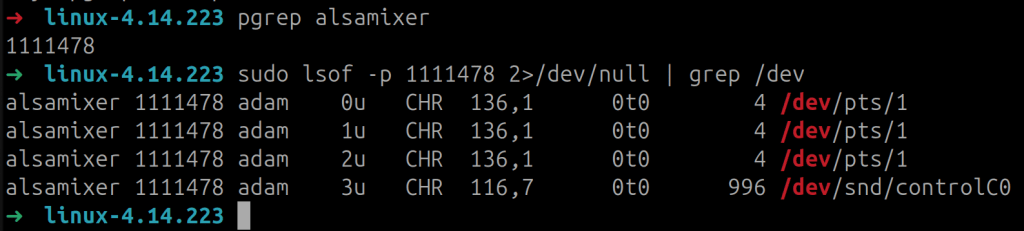

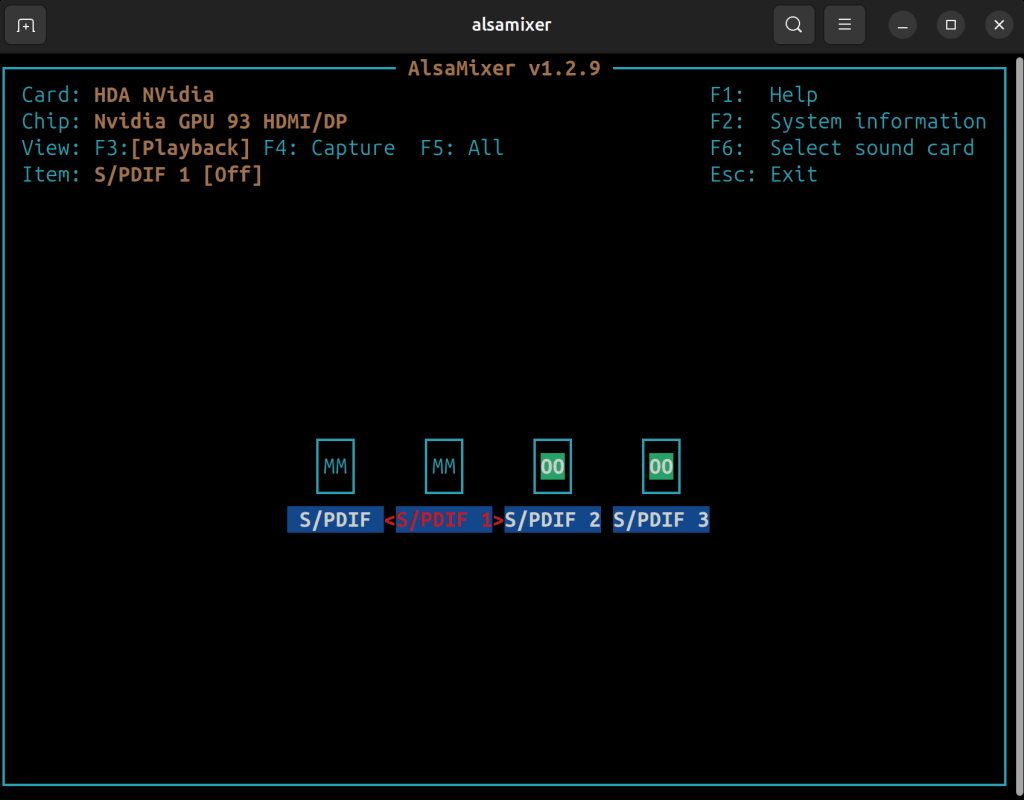

That said, my basic understanding was that this mechanism is used by utilities like alsamixer to manage system sound. To confirm this, I launched a copy of alsamixer, checked it’s open file handles, and saw it was accessing /dev/snd/controlC0. This occurred when I started adjusting sound card related settings on my laptop (see Figure 1).

During my research, I couldn’t find any easily accessible or detailed documentation explaining how this subsystem works. Honestly, when it comes to vulnerability research, you don’t always need to fully understand the purpose of the system you’re exploiting. If you can construct the right primitives (or write primitives 😆) and build an exploit chain, a deep dive into the functionality—like how sound control works in the Linux kernel—often isn’t necessary.

How are the IOCTL interfaces implemented?

To understand the vulnerability we need to understand the key differences between the 32-bit and 64-bit IOCTL handlers that are exposed by the sound control management interface. Our analysis is performed against the linux-4.14.223 release version. The source code for the sound control management interface is located within the sound/core/control.c source code file.

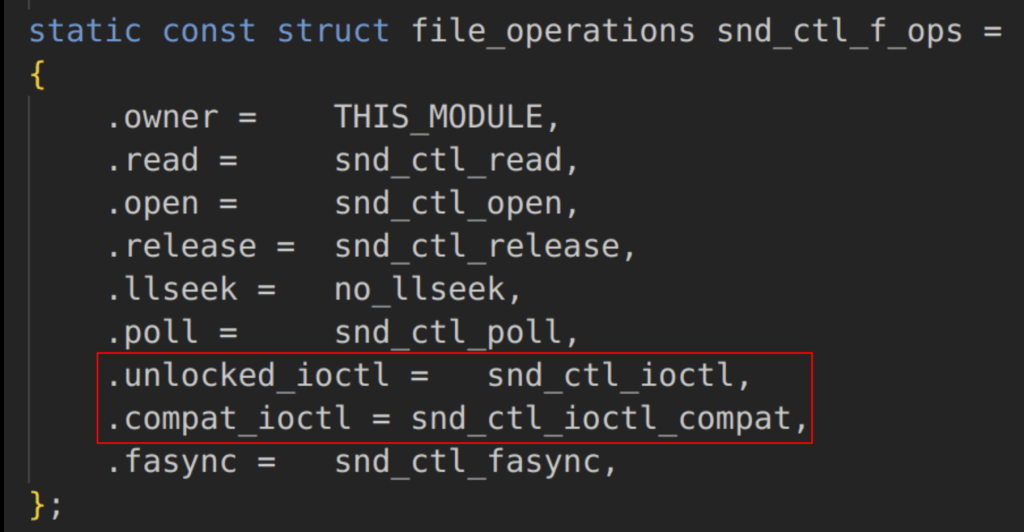

To register an IOCTL handler a file_operations structure is defined as file operations are leveraged within the Linux Kernel to interact with device drivers that expose an IOCTL interface (see Figure 3). The .unlocked_ioctl and .compat_ioctl fields within the file_operations structure are used to define the 64-bit and 32-bit IOCTL handlers respectively.

Understanding the 64-Bit IOCTL Implementation

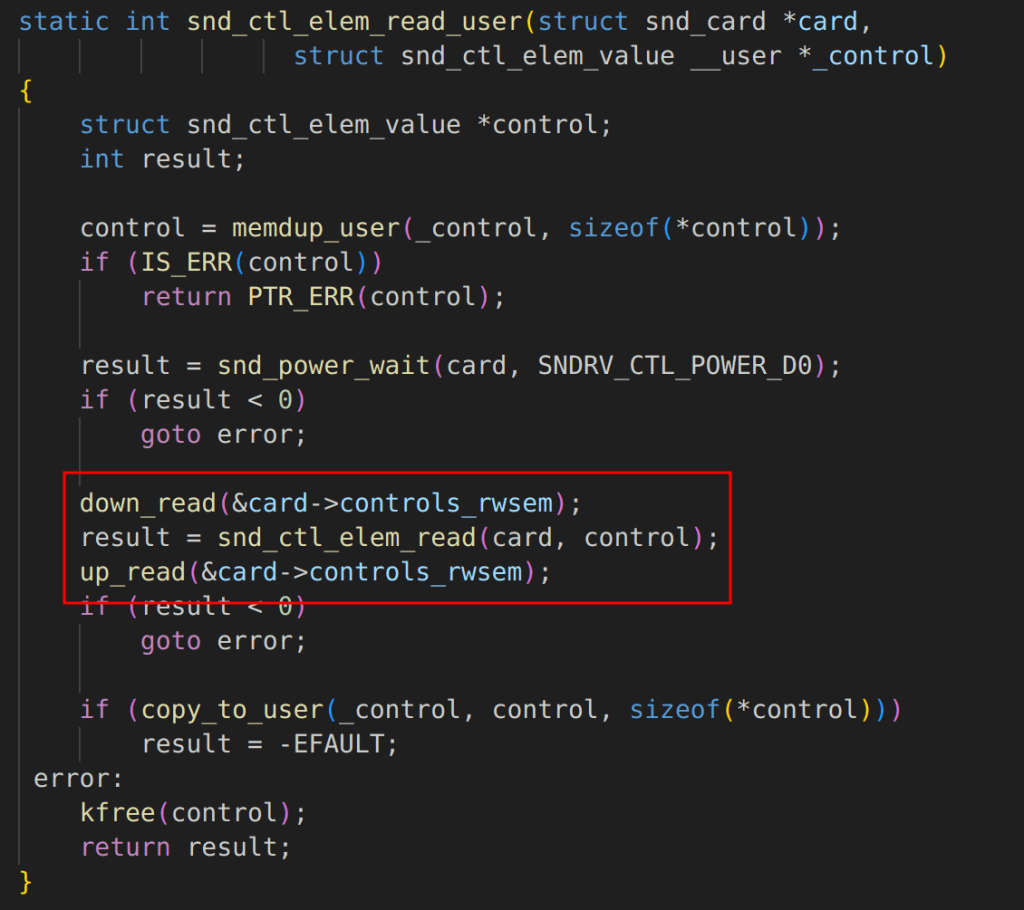

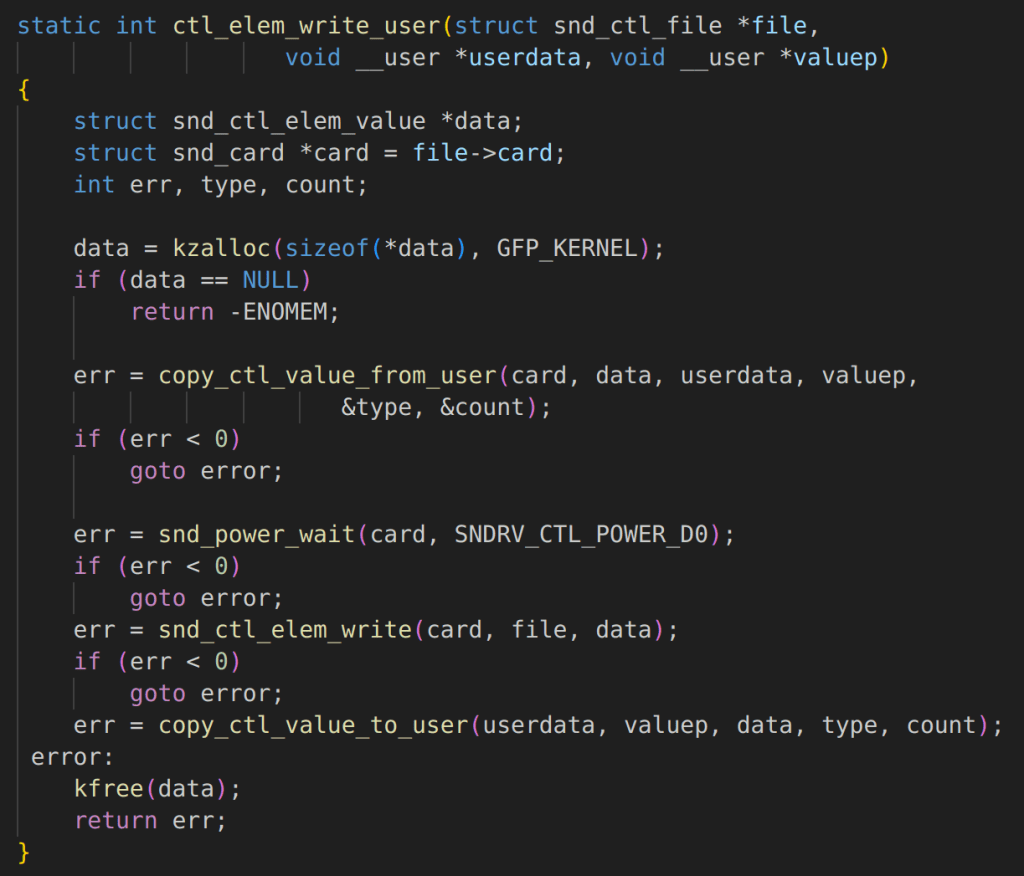

To begin we can start by analyzing the 64-bit IOCTL implementation. The IOCTL handler function is passed a IOCTL number which denotes the IOCTL handler to be executed. In this case, our focus is on the SNDRV_CTL_IOCTLM_ELEM_READ and SNDRV_CTL_IOCTL_ELEM_WRITE handlers which invoke the snd_ctl_elem_read_user and snd_ctl_elem_write_user handlers respectively.

Understanding the 32-Bit IOCTL Implementation

If we now examine the 32-bit implementation of the same handler we observe that there isn’t any locking implemented when calling snd_ctl_elem_read and snd_ctl_elem_write. Seth mentions this in his post and references the relevant commits which show how the locks were inadvertently removed as part of a code refactor. The relevant code is shown in the following figures:

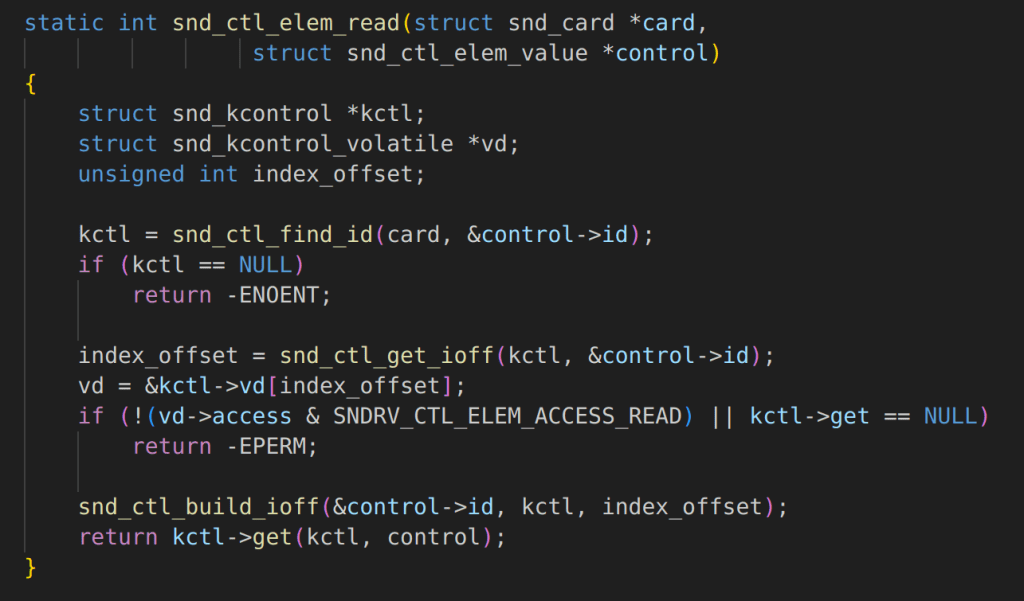

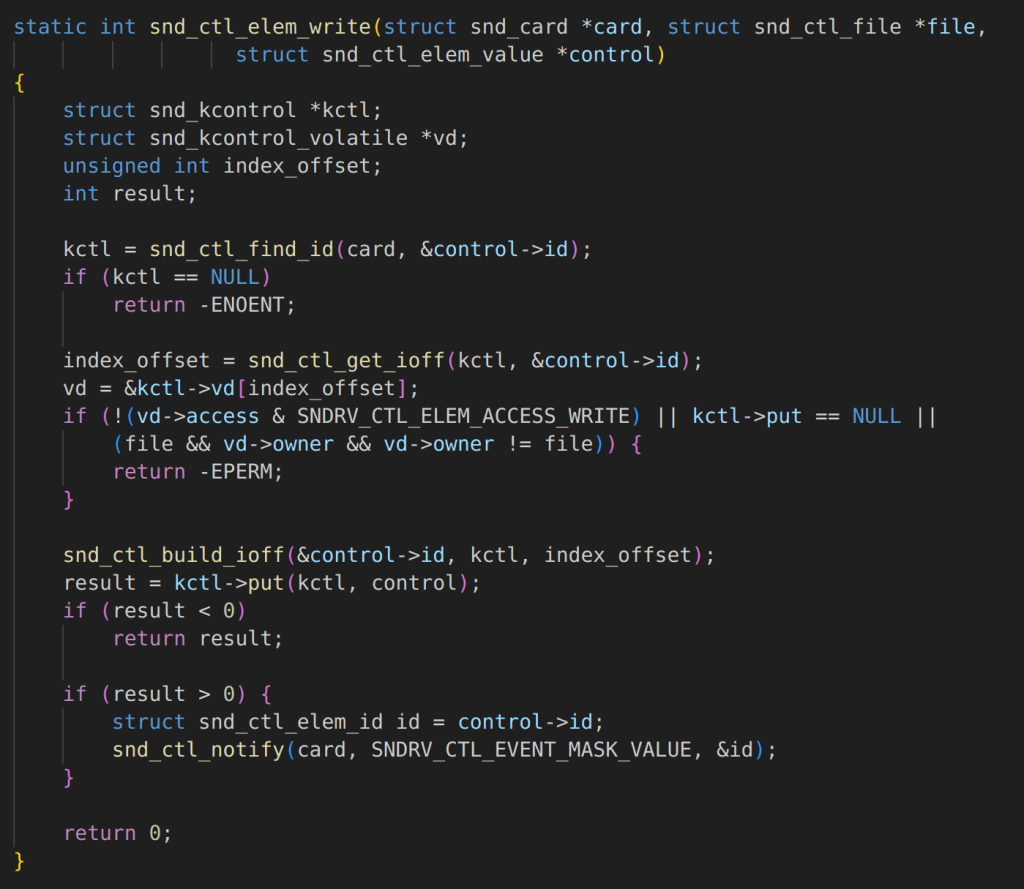

Digging into the Element Read and Write Functions

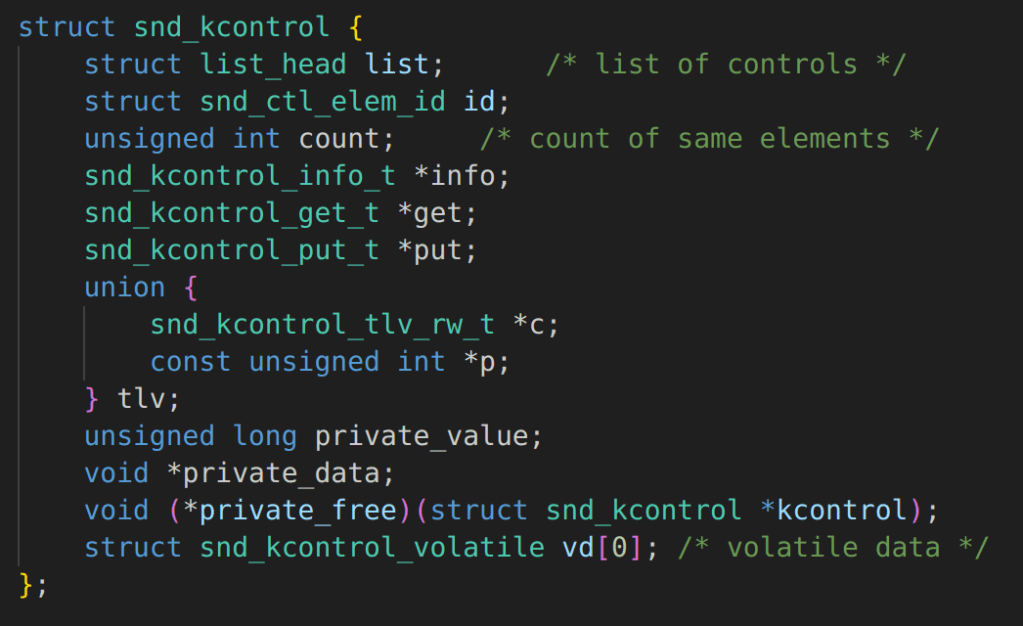

At this point, we know that there is something suspicious going on and that proper locking isn’t being used, but this doesn’t always have security implications. It could be a simple bug. However, digging deeper we quickly realize there are some serious security implications. In both snd_ctl_elem_read and snd_ctl_elem_write we lookup the control object-based on the user-provided data in snd_ctrl_elem_value.

This is used to lookup a snd_kcontrol object called kctl in the code, however, the lack of proper locking means that there is no guarantee that our sound control element hasn’t been freed and replaced with a malicious object before being used for sensitive operations. For example, in snd_ctl_elem_read a member value “get” is used by a function pointer that is an attacker-controlled value.

The attackers in the write-up produced by Project Zero leveraged two-separate vulnerabilities in the Mali GPU driver in order to exploit this particular vulnerability. However, a key difference as documented in the Project Zero write-up is that the attacker didn’t replace these function pointers and instead replaced a member value that is used when the “put” function is called to construct an arbitrary read and write primitive.

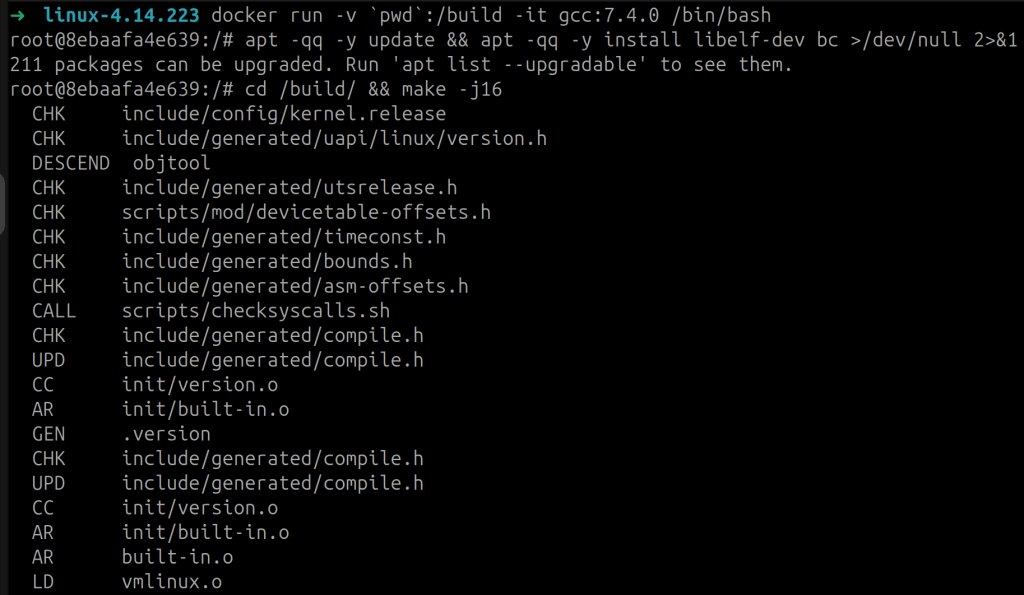

Building a Vulnerable Linux Kernel

From my testing, I’ve found that building the older-versions of the Linux kernel is rather tightly coupled with the version of GCC used to build the application. Building older kernel versions with newer versions of GCC resulted in errors at compile time. In order to work around this issue, I leveraged Docker to download an older version of GCC from DockerHub. Typically, I’ll try to target a version of GCC that was released sometime around when the kernel version I’m trying to compile was released. This allowed me to successfully build the kernel without issue (see Figure 12).

This is an important note to keep in mind as I was somewhat surprised how tightly coupled the Linux Kernel was to the version of GCC which could be leveraged to build the kernel. I believe this is because the Linux Kernel uses many advanced features of the GCC compiler within its build process and this inevitably leads to some dependencies related to specific compiler versions. When building the Linux Kernel it’s also quite useful to build in support for the 9P network file sharing protocol as this makes it easy to share files between your local computer and your test system for exploit development purposes.

Thoughts on Potential Exploitation Techniques

Exploiting this vulnerability on traditional Linux desktop or server implementations is generally significantly easier than exploiting this vulnerability on Android related systems which are often more heavily hardened and restricted from a process isolation and kernel hardening perspective. For example, I noted that a documented KASLR bypass issue within the Linux Kernel was still present within the latest version of the Linux Kernel on my personal research laptop running the latest version of Ubuntu Linux along with the research kernel I was leveraging running linux-4.14.223.

Initially, as part of this article, I thought about writing an exploit for this vulnerability. However, after reflecting, I decided it would be better to move onto analyzing another vulnerability. The exploitation of this issue is rather complex as the attacker uses other vulnerabilities to get the proper primitives needed (e.g. for heap spraying) and I decided I’m more interested in documenting additional bug-classes than spending an extended period of time on the exploitation side.

Although, one of the things I’ve been having fun lately is leveraged the pwn.college site for messing around with Linux Kernel Exploitation. They have a lot of fun challenges you can complete using an intentionally vulnerable driver that does a decent job of teaching you various exploitation techniques. For example, one of the challenges involves using a use-after-free vulnerability to overwrite a msg_msg object to construct an arbitrary read primitive and then triggering the issue again to overwrite another struct to trigger a ROP chain to elevate process privileges.

Conclusion

It’s fascinating to see, through the Project Zero write-up, just how much time and expertise is invested into building capabilities likely meant for government use in counter-terrorism and counter-intelligence. It might seem surprising that n-day vulnerabilities still succeed in these contexts—but when you’re targeting individuals paranoid enough to avoid installing updates out of fear they contain backdoors, it makes more sense.

The level of sophistication behind these exploit chains—backed by what are essentially defense-industrial-complex-grade resources—feels like a whole different world compared to what many red teamers experience. Most of us are out here compromising Fortune 500 companies with the technical equivalent of a slingshot and a homemade Molotov cocktail. Lina Lau’s An Inside Look at NSA (Equation Group) TTPs from China’s Lens, alongside the Project Zero analysis, gives a rare peek into that parallel universe.

I can only imagine what it’s like to run offensive operations with that kind of firepower. Still, there’s something satisfying about working with limited tools—because the asymmetric nature of offensive cyber means that even the underdog can hit above their weight. To be honest, I’m not entirely sure where I’ll take this series next. I’ve just been working on it for fun in my free time, and I’ll probably keep following whatever feels most interesting on any given weekend. I’ve found that’s usually a better approach than forcing specific goals—especially when it’s meant to be something enjoyable. No pressure, just curiosity.

Leave a comment