Overview

Recently, I had a chance to present on DEF CON and Black Hat on my research into tunneling traffic through web conferencing systems such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams. During my DEF CON talk, I discussed some factors impacting traffic tunneling speeds and data exfiltration speeds that are probably fairly counter intuitive if you aren’t familiar with how Internet routing works. To be completely honestly, I also wasn’t familiar with a lot of this stuff until I ran into some interesting behavior during my research.

In this article, I would like to expand a little bit about what I’ve learned about Internet routing and interesting things I’ve observed. There are some interesting things I discovered during this research, for example, did you know that connecting to ExpressVPN can sometimes double or even triple your download speeds in certain scenarios? Did you know that peer-to-peer connections can sometimes be slower than using a centralized server?

The Last Mile as a Historical Bottleneck

I grew up in rural Iowa, where DSL came over copper lines strung between wooden poles—and we basically knew the phone line repair guy by name. The connection didn’t usually go out completely, but if it rained too hard or the wind blew the wrong way, we’d start seeing packet loss or huge latency spikes. Sometimes mice chewed through the insulation in the phone box, and you’d notice not because the internet died, but because your ping jumped from 80ms to 800ms. That was just normal. Back then, I’d queue up OpenBSD ISO downloads, 512 MB monsters, and let them run overnight, praying the line held up long enough to finish before sunrise. Every byte felt earned. At one point we purchased two lines and were able to multiplex our traffic over two redundant phone cables in order to improve speeds (it worked, kind of, but not really).

These days, things are better. Thanks to recent infrastructure investments, our area has a line-of-sight tower that beams internet to nearby homes—and it’s fed by fiber. It’s not blazing-fast by urban standards, but it’s stable, low-latency, and way more reliable than the old copper lines. No more praying for clear weather to download a patch file. It just works. The last mile, at least in rural Iowa, finally got an upgrade. My dad mentioned that they’re now rolling out fiber-to-the-home in some of the neighboring towns, and our area should be next. It’s kind of surreal, growing up, the idea of getting fiber in rural Iowa would’ve sounded like a joke. The same place where we used to fight for stable DSL in the rain might soon have gigabit fiber straight to the living room.

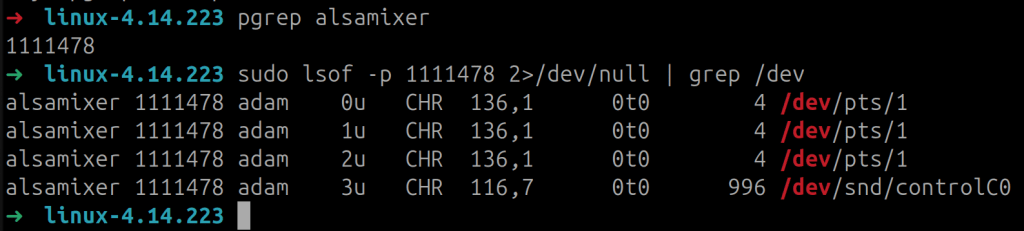

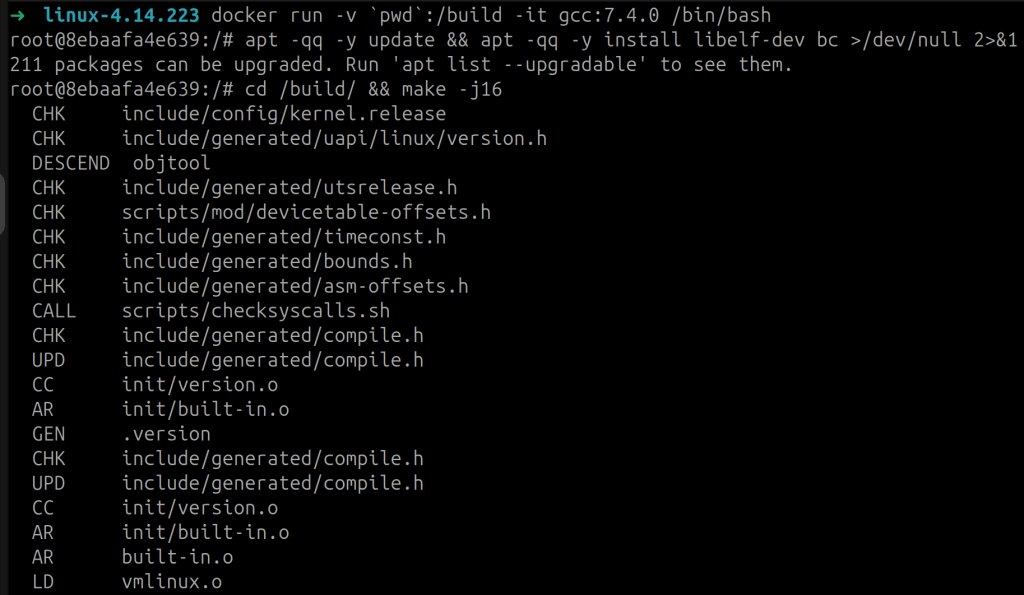

Figure 1: An Internet speed test I ran from my parent’s house in rural Iowa which leverages a line of site connection that typically averages around 40 mbps download speeds through the last-mile to a speed test server hosted on my Internet service providers network.

Anyway, this is mostly just a long-winded way of saying: the way we think about internet speeds—what’s fast, what’s slow, and where the bottlenecks live—doesn’t always map to how the internet actually works today. It’s not just about your connection speed anymore. Routing paths, international transit, peering relationships, and VPN exit nodes can have a far bigger impact on performance than the number on your speed test.

Setting the Stage: Compromising the Helpdesk

One of the things that I’ve seen leveraged very successfully on red team engagements is compromising the helpdesk to gain a foothold within the organization. In many cases, the helpdesk is a very fruitful target in most organizations. It’s often staffed with entry-level IT technician who are often fairly early in their career and don’t yet have strong technical skills. Additionally, they have a strong incentive to solve user problems as they are often rated on their performance within ticketing and user survey systems.

My colleague Anthony Paimany actually wrote an amazing technical blog post on the Praetorian blog on this topic titled Helpdesk Telephone Attack: How to Close Process and Technology Gaps. We’ve also seen many real-world threat actors targeting this infrastructure. Some notable examples include attacks documented by CISA and Google on the Scattered Spider threat actor.

An interesting problem that we often run into in these scenarios is that, especially with large multinational companies, it’s not uncommon for them to leverage helpdesk staff across the world from the United States to India. This is often done for motivations like cost savings or just due to them being multinational corporations with a workforce that spans the entire globe. Often post-compromise after implanting these user devices we will note slow tunneling speeds through these users systems.

Intuitively, especially if you are like me and grew up with slow DSL connections, it’s easy to assume that maybe these users are on a slow last-mile connection or even something like DSL if they are working from home within a rural area. However, the reality is quite different as the cost of fiber has gone down significantly many middle-income countries like India, Thailand, and Malaysia have invested heavily in building out robust fiber to the home infrastructure. Often, the bottleneck isn’t actually the user’s last mile but poor international peering, budget transit providers with oversold capacity, packet loss, and other factors upstream from the victim user.

Understanding the Architecture of the Internet

My first exposure to the concept of networking was from reading my mom’s textbooks on computer networking. I was in eighth-grade and she was completing a health information technology degree at DMACC which is a local community college in Iowa. It was fascinating to me at the time learning about TCP, UDP, and the basic building blocks that make up the Internet.

I learned a lot from reading the book, but when talking about the Internet it often referred to it as this sort of abstract cloud without really going into details. Kind of this decentralized black box that connected everything, but the book didn’t really discuss in-depth how this all actually came together. If I had to guess I think this is probably how many of us learned about the Internet as well and unless you are a network engineer you likely don’t have a strong understanding of these concepts.

In practice, the Internet isn’t really this decentralized black box at all. It’s actually a patchwork of very real infrastructure—fiber optic cables laid across oceans, routers owned by private companies and ISPs, and a surprisingly political and hierarchical system of agreements and routing decisions that govern how data flows.

So, while it feels like the Internet is this seamless web, it’s really a complex, semi-centralized system held together by a mix of engineering standards, corporate agreements, and a good dose of human error. If anything, the more you learn about it, the more remarkable it becomes that it works as well as it does.

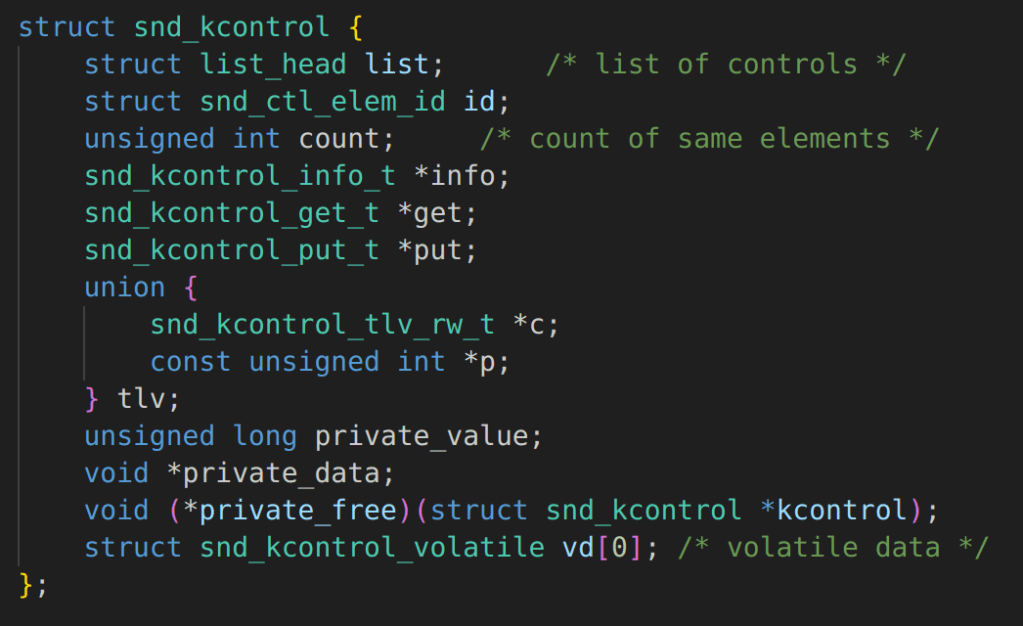

Wikipedia has this awesome diagram shown below in their Tier 1 network article which outlines what a modern Internet architecture typically looks like with multiple-levels of Internet service providers. Often, what you think of as your Internet service provider is actually a smaller tier 3 Internet service provider that hands off most traffic to tier 2 and tier 1 network service providers.

Figure 2: A diagram of the Internet showing tier 1, tier 2, and tier 3 internet service providers with direct peering relationships with hyperscalers and major Internet providers along with Internet exchange points used to connect content providers and regional Internet service providers.

Internet traffic across continents often flows under submarine cables laid across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In the case of my parents, our Internet service provider is likely a smaller tier 3 Internet service provide which deploys last-mile fiber infrastructure and point-to-point communication towers. These types of providers often hand traffic off to a tier 2 or tier 1 Internet service provider for transit outside of their network.

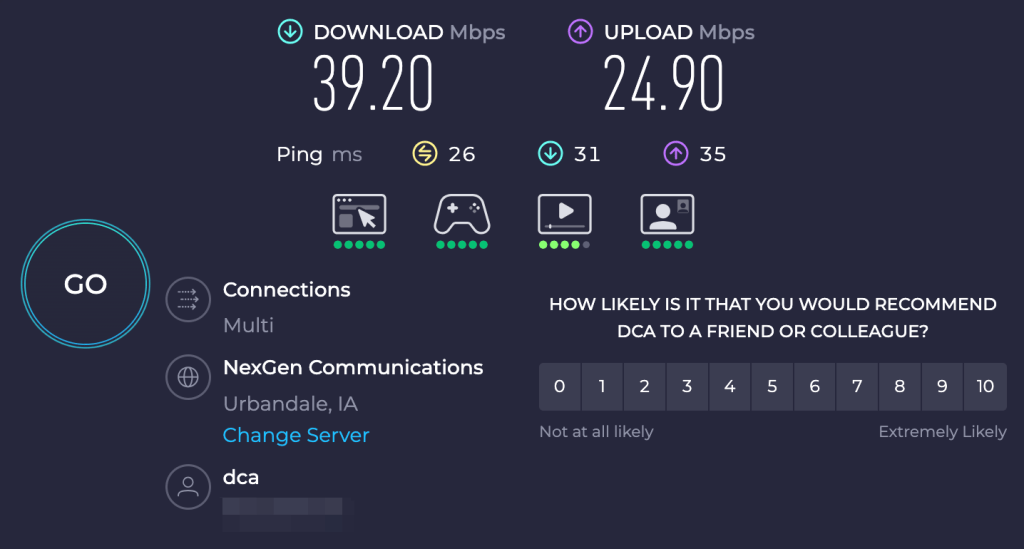

This is an expense for many Internet service providers and most providers don’t pay for premium international transit on international routing as it can often be expensive and this doesn’t typically impact performance for the average user. Figure 3 shows a diagram from submarinecablemap.com which shows some of the undersea cable systems that exist connecting the United States with countries in Asia such as Japan, Singapore, China, etc.

Figure 3: A diagram from submarinecablemap.com showing deep sea cables that connect the United States and Asia.

Often, these residential tier 3 Internet service providers will purchase cheap wholesale international transit from upstream internet service providers for international or regional routing depending on the size of the provider. For international transit on residential connections, it’s common for providers to leverage budget or cheaper providers for transit in order to save money.

For the average user, this doesn’t really impact performance a ton as most websites targeting an international audience are using content delivery networks (CDNs) like Cloudflare which have global points of peering and excellent peering with internet service providers and internet exchange points within their respective regions.

However, as an attacker this is something we need to keep in mind depending on how we are constructing our infrastructure. For example, if we are using budget virtual private servers as dumb relays to our backend infrastructure these types of providers often don’t pay for premium transit. This could mean that our data exfiltration or tunneling speeds end up being artificially slow due to poor transit between our relay and the victim user.

Analyzing Rural Iowa to Singapore Routing

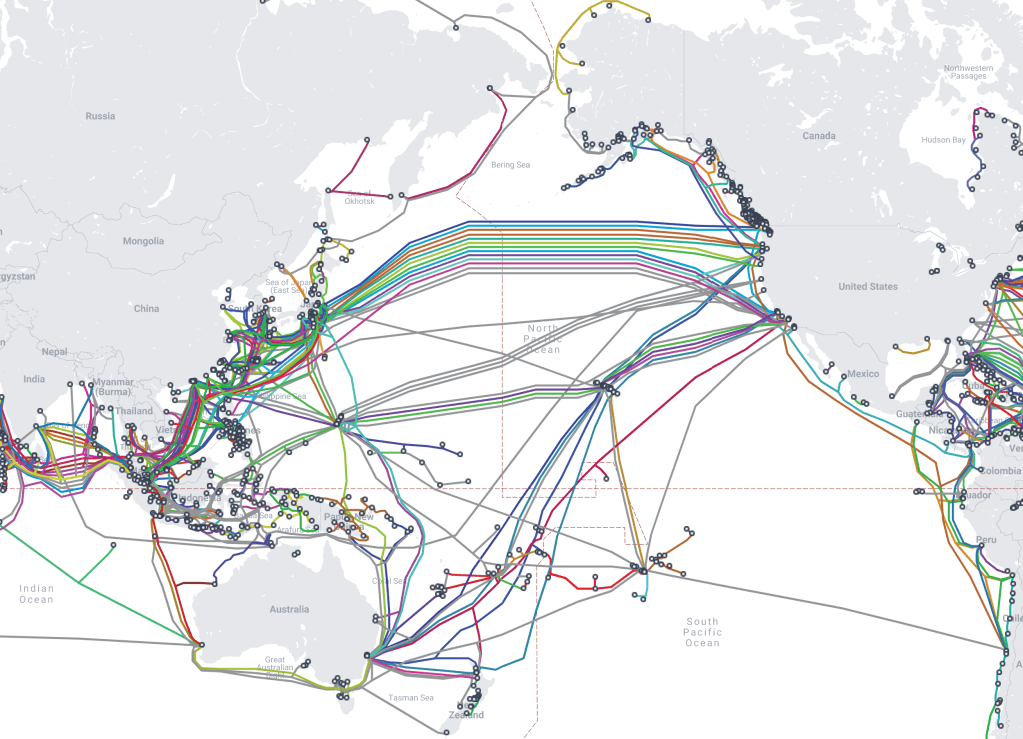

At the moment, I’m visiting family in Iowa and wanted to play around with routing a bit running tests from my families Internet service provider to different locations. I’m going to demonstrate this by downloading a test file from a Hetzner server located in Singapore from rural Iowa. In this scenario, I’ll leverage an ExpressVPN server to modify the way my packets get routed outside of the United States and how better transit can double the download speeds from a remote server even when the last mile connection remains the same.

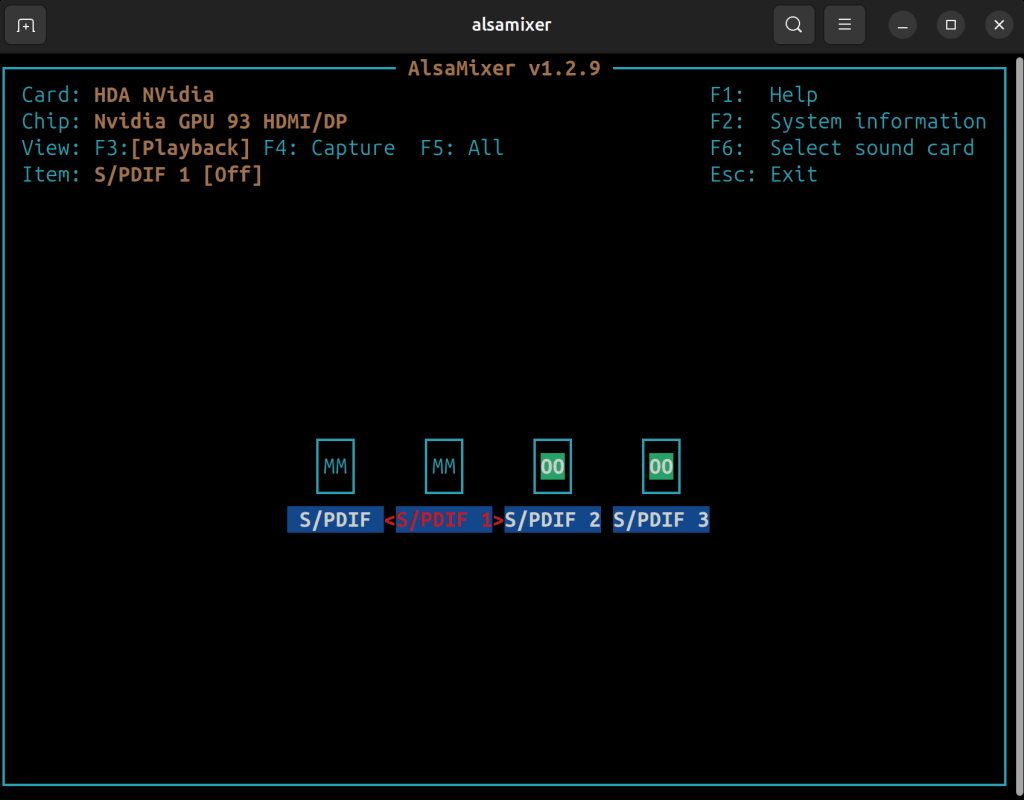

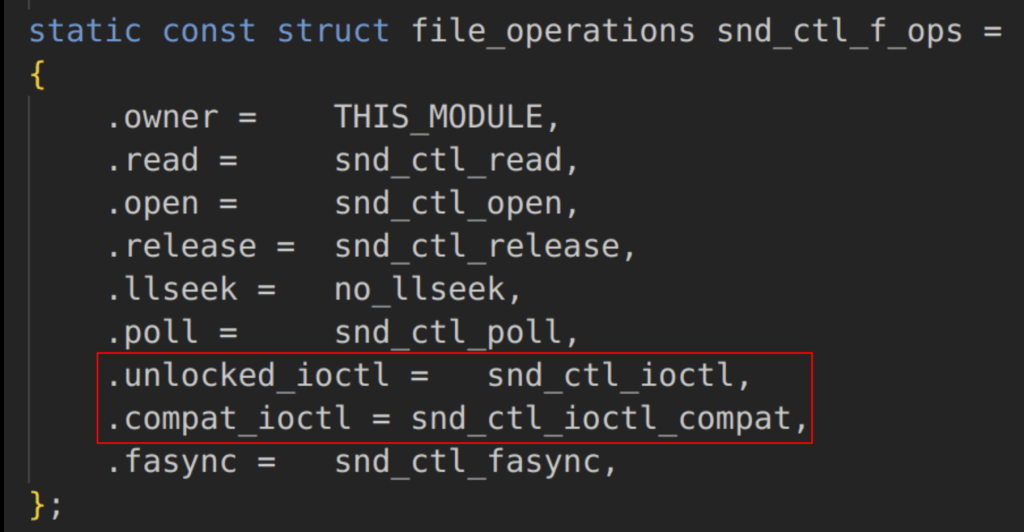

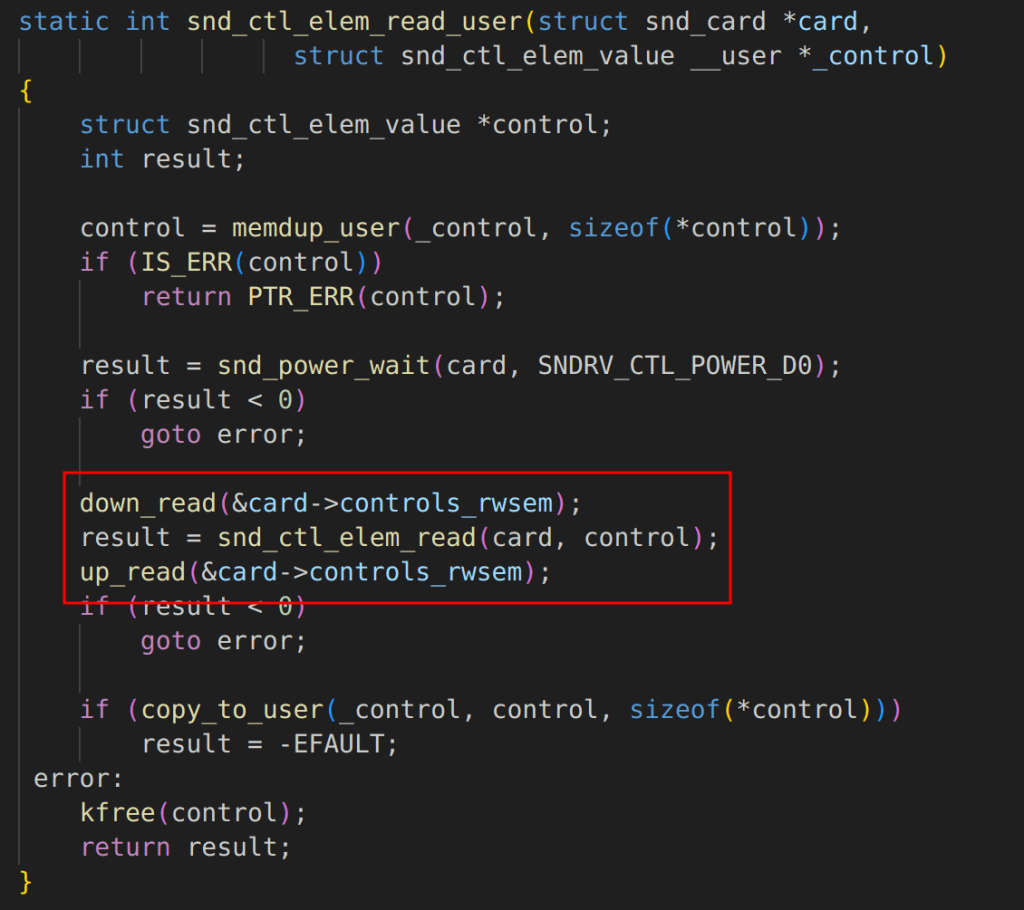

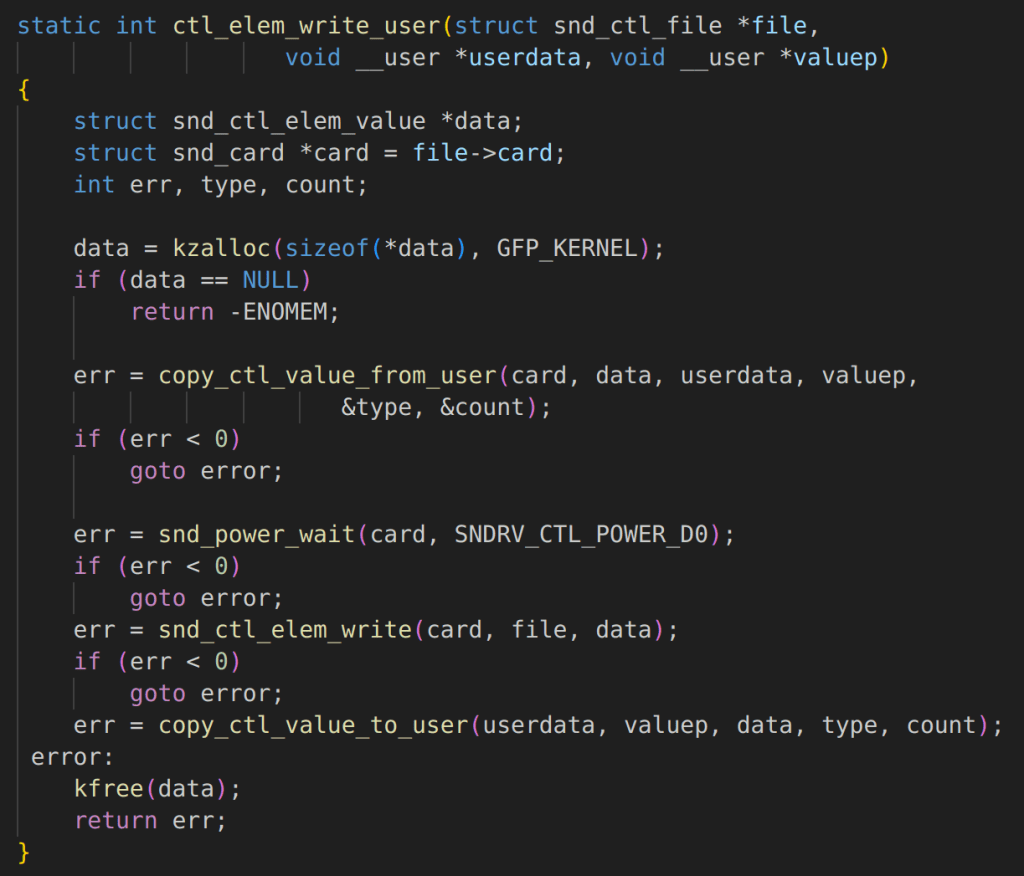

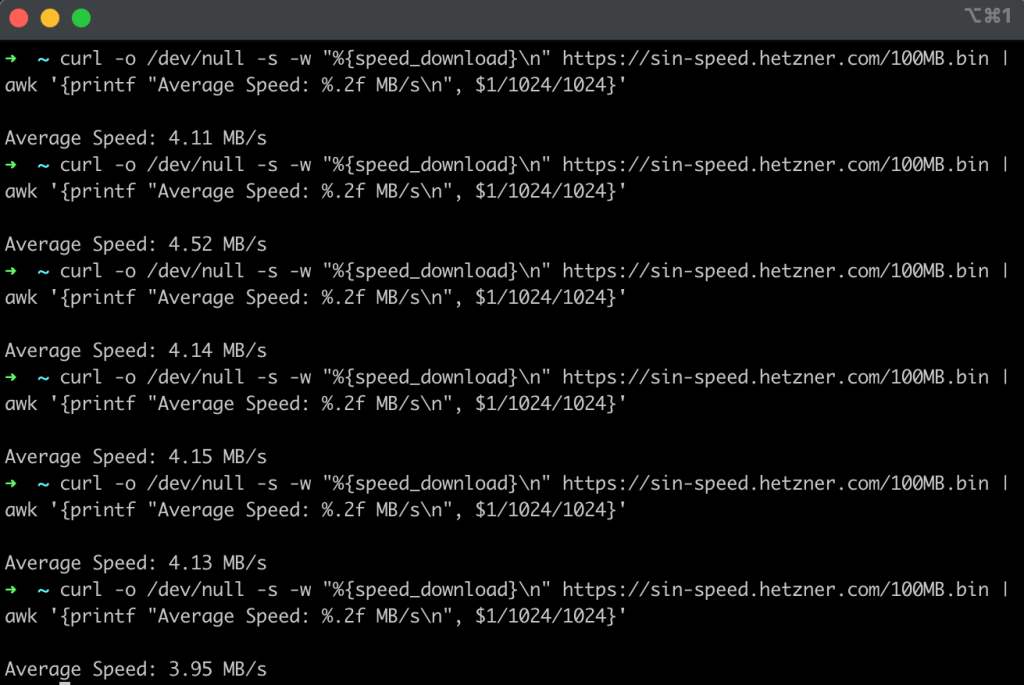

If we dig into Figure 4 we observe that our average download speed in this scenario is around 2.0 MB/s which is about half of what I was getting doing a speed test against a server hosted in my Internet service providers network which averages around 5.0 MB/s from the last-mile to a server directly on the Internet service providers network (refer back to Figure 1).

Figure 4: An example set of tests performed using curl testing download speeds downloading a 100 MB test file from Singapore with an average speed of around 2.0 MB/s.

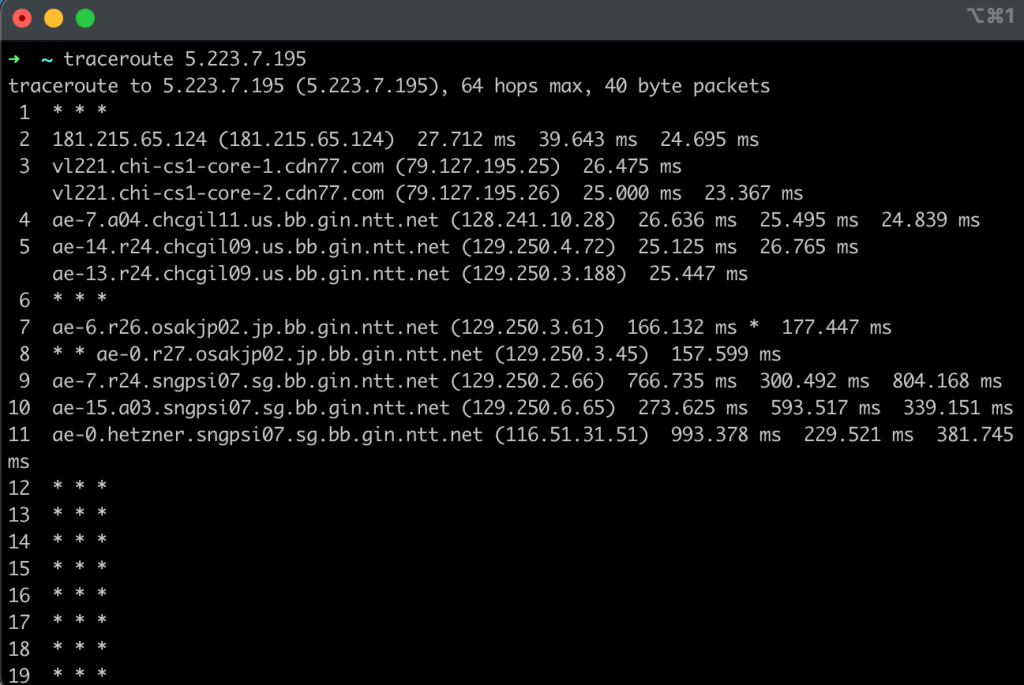

After running this test I ran a traceroute in order to determine how my traffic is routed after it leaves the network, is transmitted to the point-to-point tower, and then routed through a fiber optic connection to my Internet service provide who then hands the traffic off to an upstream transit provider to route the traffic domestically and internationally.

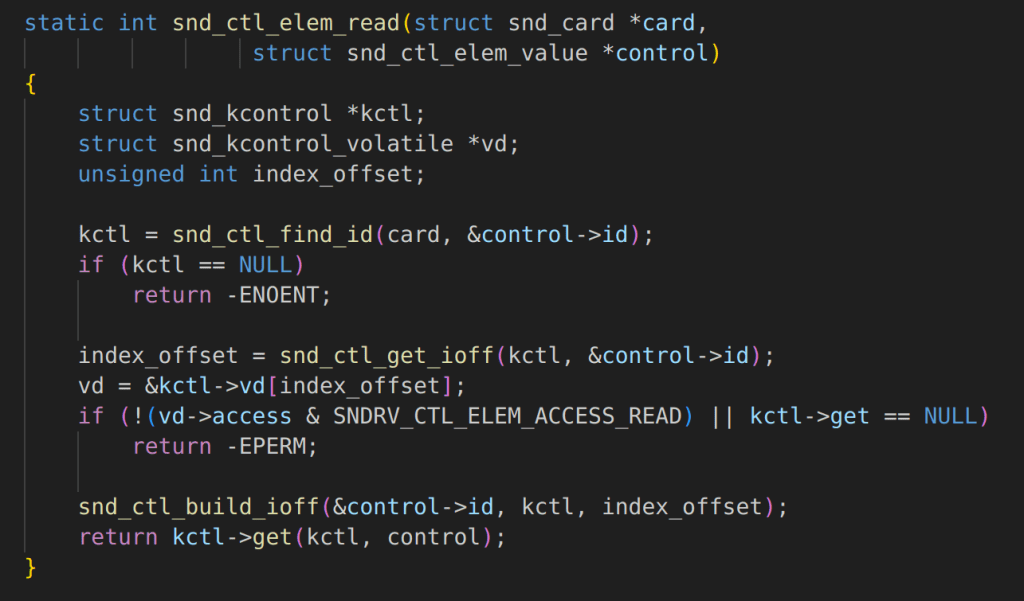

Again, I’m not an expert on this stuff, but if we look at Figure 5, we can see a bunch of RFC1918 internal addresses for the first couple of hops as I egress out of my home network and to the internet service providers network. From what I can tell, it looks like my Internet service provider in this scenario is then handing the traffic off to another provider (dcaonline.com) which then transfers the data to Hurricane Electric where it is routed internationally to Singapore and handed off to ViewQwest (vqbn.com.sg) which appears to be an ISP in Singapore.

Figure 5: A traceroute to the Hetzner region in Singapore from my connection in Iowa without routing the traffic through any sort of VPN in order to modify how the traffic is routed internationally.

Leveraging ExpressVPN to Modify Transit and Routing

At this point, there is actually something magical we can do to increase speeds and this completely blew my mind once I figured out that this would actually work. Basically, if your Internet service provider isn’t also a tier one-service provider they are going to need to pay someone else to route your traffic internationally (and even if they were a tier one provider they probably aren’t going to give you premium transit for free as a residential internet user). This costs them money and, in particular for residential connections, the provider is going to more than likely assume that most users are routing to common websites like Netflix or YouTube which likely have localized points of presence within their respective regions.

Thus, they are probably going to purchase budget transit at wholesale prices for routing internationally and in many cases these transit providers oversell capacity to multiple providers under the assumption that things will mostly be fine. Unfortunately, this often means connections from say residential internet connections are likely going to leverage subpar transit in many cases. Please note, that this is a generalization and not every residential Internet provider uses budget or low-cost transit provider to save on costs, some may for one reason or another pay for premium transit even for residential users.

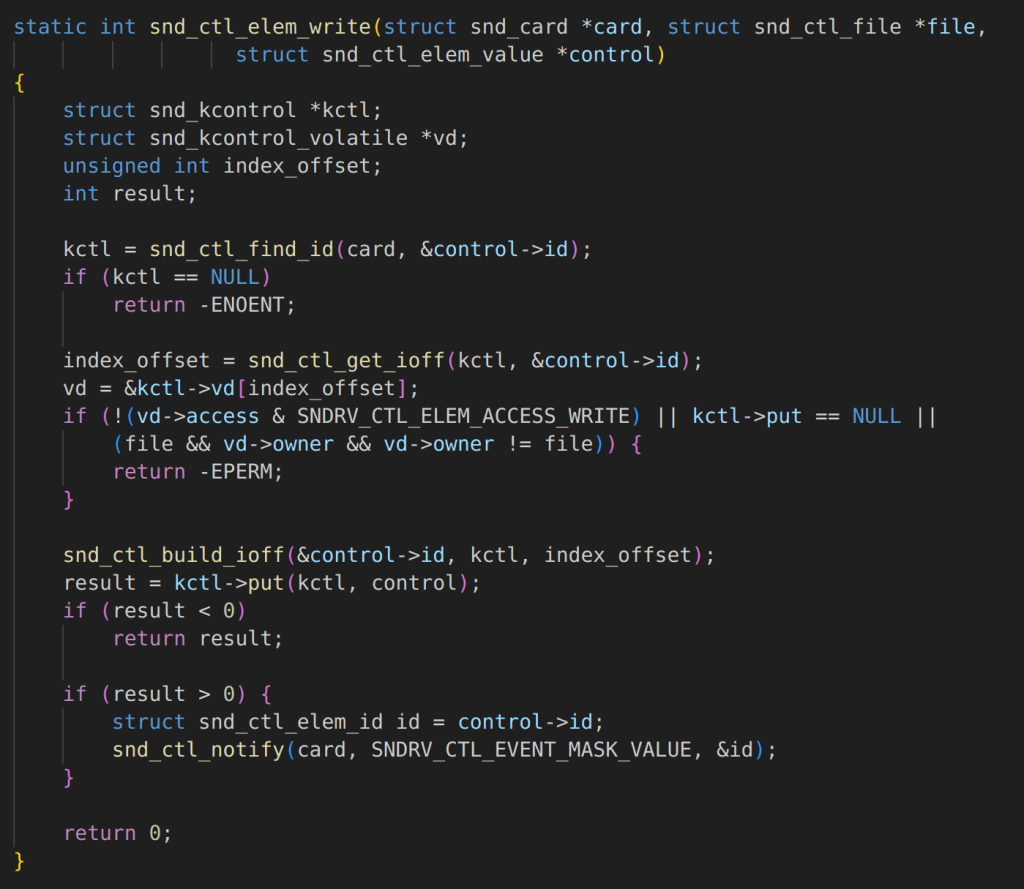

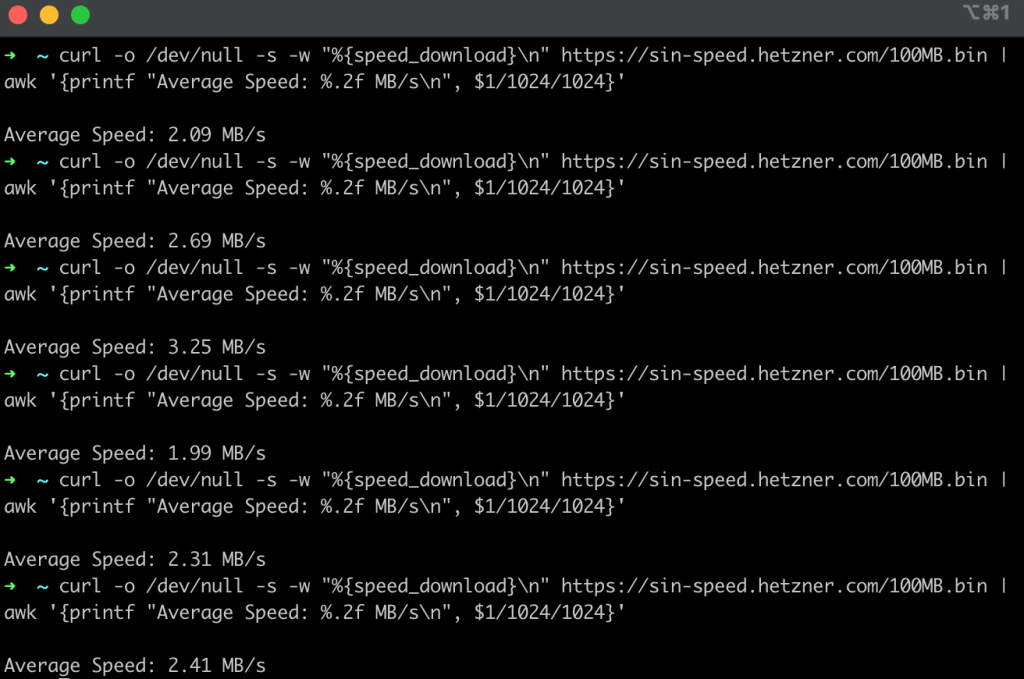

In this section, I’m going to discuss how we can leverage ExpressVPN in order to double our download speeds from the Hetzner server in Singapore without changing anything about the connection. I’m still on the same point-to-point connection in rural Iowa and the only thing I’m going to change is that I’m going to first route my traffic through an ExpressVPN server in Chicago 300 miles away from my current location. Across six different tests we observe that our download speed is about twice as fast as it was when we were downloading this file directly from our home network connection (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: An average download speed of roughly 4.0 MB/s was achieved downloading the same file by first routing through an ExpressVPN server within Chicago.

If we run traceroute while connected to ExpressVPN we can observe the path that it takes when routing internationally to Singapore. In this scenario, we observe that our traffic is routing differently and leveraged NTT as opposed to Hurricane Electric as a long-haul transit provider.

Figure 7: A traceroute showing my traffic being routed from my home network to Singapore, but this time leveraging NTT as a transit provider for long-haul international transit.

From my perspective, there are likely around two-to-three factors allowing me to achieve faster download speeds routing through ExpressVPN compared to downloading the same file from my home network.

- Good Connectivity to the VPN Server: In order for this to work and allow me to achieve faster speeds my domestic internet service provider needs to have good connectivity to the ExpressVPN server. If there is not good peering or connectivity to the ExpressVPN server I’m connecting to this will become the bottleneck even if whatever routing we take internationally ends up being faster.

- Premium International Transit: It’s likely that ExpressVPN is paying for better quality transit compared to my residential internet service provider. Many residential providers are focused on optimizing for common, high-traffic destinations like YouTube, Netflix, and major content delivery networks (CDNs) such as Cloudflare. They are often less concerned with the performance of diverse, international routing, which a global VPN provider must prioritize to deliver a consistent service.

- Lower Packet Loss: The paths we take through ExpressVPN using NTT are likely using more premium tiers of transit with higher priority and lower packet loss. From what I have observed, the TCP protocol is quite sensitive to packet loss and latency which can trigger congestion mechanisms and result in reduced transfer speeds.

Peer to Peer: Is it always faster?

There are some interesting conclusions that we can draw from this as well which are relevant to my research into tunneling traffic through web conferencing infrastructure. For example, these solutions often support traffic tunneling through both direct peer-to-peer communication and through a centralized media server. Many people may think that the peer-to-peer route is always ideal if the meeting size is say two participants, however, this is not always true and depends on many factors.

For example, imagine a scenario where you have two users on AT&T’s network in Austin, Texas who are working from home and need to join a video call. In this scenario, a peer to peer connection is likely more efficient as both users can route to each other via NAT hole-punching and communicate with each other using AT&T’s network in Austin. However, in this same scenario where one user is say in the United States and the other user is in India on residential connections it’s likely that peer-to-peer communication would be slower than leveraging a centralized media server.

This is likely true for several reasons which we’ve touched on already such as the increasingly centralized nature of the Internet and the fact that most residential internet providers are not going to prioritize purchasing premium international transit for residential users. In this scenario, if you were to say leverage a centralized Microsoft Teams media server this would likely be more efficient as each user would be connecting into Microsoft’s network using their localized point-of-presence while routing over Microsoft’s private backbone which is likely to have significantly better performance.

Performance Issues with TCP Based Transports

During my research into web conferencing tunneling, I designed a utility called turnt which we could leverage for tunneling traffic through web conferencing infrastructure. While I was designing the tool I considered different tunneling mechanisms. One of my ideas was to implement full VPN tunneling with the outer channel being TURN over TLS over 443/TCP and the inner channel being a tunnel that supported full VPN style tunneling of TCP and UDP traffic.

Ultimately, I made the decision that I would rather implement SOCKS proxying compared to things like full traffic VPN tunneling due to issues such as the TCP meltdown issue which occurs when tunneling TCP traffic within an outer TCP layer. In this section, I’d like to describe a few of the performance issues you can run into with TCP traffic that you don’t encounter with UDP traffic:

- TCP Meltdown: As mentioned before tunneling TCP traffic over a TCP tunnel can often cause major performance issues. Computerphile has an excellent video on the TCP Meltdown issue.

- Head of Line Blocking: Head-of-line blocking is an issue that arises due to TCP’s requirement for in-order delivery which means any packet loss blocks receiving of the packets behind the lost packet until the lost packet is re-transmitted.

- Packet Loss and Latency: I’ve also found that TCP transmission speed is much more heavily impacted by latency and packet loss than most UDP connections.

In the subsequent sections, we will provide some advice on how to handle these scenarios when performing offensive operations and how attackers can benefit from thinking like network engineers in certain scenarios.

Advice for Offensive Operations

I hope at this point you have realized that understanding some of the nuances behind Internet routing is actually very important as red teamers and network operators. Whether you are trying to tunnel traffic through a victim endpoint or simulate efficient large-scale data exfiltration during a red team engagement, understanding Internet routing is crucial to maximizing performance.

From my perspective, there are a wide variety of scenarios where red team operators could benefit from thinking like a network engineer from traffic tunneling through victim systems to data exfiltration. I’d like to provide a few recommendations in this section for red team operators on how they can use the ideas covered in this article on their own real-world red team engagements:

Intelligent Data Exfiltration

A lot of the scenarios we’ve discussed in this article involve international routing where your internet service provider doesn’t have good or direct peering with adjacent providers. However, even when routing between domestic servers within the United States there can still be speed bottlenecks for a variety of reasons. For example, sometimes hyperscalers and other content providers have disagreements with internet service providers about things like paid peering relationships. This can cause providers to either throttle traffic to certain systems or send it over more congested public routes that hinder connection speeds. When doing things like

Avoid Tunneling TCP over TCP (TCP Meltdown)

From any sort of tunneling or exfiltration perspective you really want to be careful with tunneling TCP traffic over TCP channels due to the TCP Meltdown issue mentioned previously. I wanted to quickly demonstrate this just to make it a little bit more real.

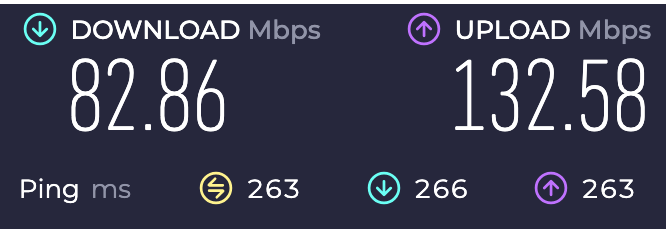

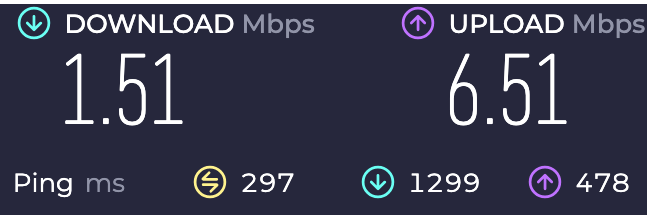

Basically, in this scenario I’ve got a VPN server running in GCP with both UDP and TCP ports that you can connect to in order to establish a VPN connection. Figure 8 shows the speed results when using UDP as the outer transport for an inner traffic tunnel with a TCP connection. Figure 9 shows the speed test results when using TCP as an outer layer for an inner TCP tunnel.

Figure 8: An example Internet speed test performed using UDP as a transport for a VPN connection and then routing traffic over HTTPS on 443/TCP to perform an Internet speed test.

Figure 9: An example Internet speed test performed using TCP as a transport for a VPN connection and then routing traffic over HTTP on 443/TCP to perform an Internet speed test.

In this scenario, we used the same last mile connection and performed these connection speed test just minutes apart with vastly different results. The same routing was used in both scenarios, but the approach to tunneling traffic at the transport layer had a huge impact on connection tunneling speeds. Having these types of TCP services enabled on your VPN is useful when your users are in environments with restrictive egress controls, but in most scenarios it will vastly hinder download speeds relative to UDP tunneling performance.

Riding Provider Network Backbones

One underrated tactic for improving command-and-control (C2) reliability and speed is leveraging the private backbones of major cloud or application providers. For example, tunneling traffic through platforms like Microsoft Teams or similar services allows your packets to ride over Microsoft’s globally distributed private network, which has robust connectivity and excellent international transit performance.

This can dramatically outperform budget VPS providers like Hetzner or OVH for relay infrastructure. While those providers are popular and affordable, they often depend on congested public transit routes or regional peering arrangements that may introduce latency, packet loss, or asymmetric routing paths — especially for victims located far from the VPS region.

In contrast, platforms with tier-1 peering and private backbones (e.g., Microsoft, Google, Cloudflare, Amazon) typically:

- Use well-maintained, high-performance international transit links

- Offer strong peering relationships with local ISPs

- Provide low jitter, high availability paths from diverse global endpoints

If you’re setting up global infrastructure, consider placing your relays or staging servers behind these networks (e.g., in Azure or using SaaS tunnels) to benefit from their transit quality. It can make C2 channels far more responsive and less likely to drop or degrade under suboptimal Internet conditions — especially in regions with poor Internet infrastructure.

Egressing TCP Traffic Close to the Victim Server

This one is a bit more speculative, but I wanted to share an observation that’s repeatedly come up in my own testing: when downloading large amounts of data over a VPN, it’s often significantly faster to egress TCP traffic near the destination server—even if that means connecting to a VPN node geographically far from me.

At first glance, that seems counter-intuitive. You’d think routing through a local VPN node (e.g., an ExpressVPN server in the same region as you) would offer better performance. But in some cases, I’ve found that connecting to a VPN server closer to the target server—not to me—can increase download speeds by 50–60%.

I have a few working theories:

- ExpressVPN uses CDN77 as its infrastructure partner, and CDN77 has a robust, well-peered global network. When I connect to an ExpressVPN server “far away,” the actual tunnel entrance is often very local—I see via traceroute that I’m entering the VPN through a nearby CDN77 point of presence (POP), then being routed through high-performance backbones to the final VPN endpoint.

- These tunnels appear to operate over UDP, which is less sensitive to jitter and packet loss than TCP. This means my outbound connection to the distant VPN server is fast and efficient, even if it crosses continents.

- Once the VPN server egresses my traffic close to the target system, the TCP connection from the VPN node to the target server benefits from low-latency, low-loss conditions. This seems to dramatically improve bulk download performance.

The core idea is that TCP is very sensitive to latency and packet loss due to how congestion control and retransmissions work. If the traffic from my local machine to the target server has to traverse many international hops, the likelihood of retransmissions and window scaling bottlenecks increases. But if I offload the TCP portion to occur within a single region or high-performance link close to the target, and then let a VPN tunnel (over UDP) carry the payloads back to me, I get better throughput overall.

To be clear, this is based on empirical testing—I haven’t fully verified every step of this routing behavior, and I’d love to dive deeper into the mechanics in the future. But if you’re doing red team work and pulling large volumes of data during an engagement, try tunneling through a VPN node close to your target’s region. You might see surprisingly better speeds.

Random Thoughts on TOR and Anonymous VPNs

This section is less directly relevant to red teamers conducting ethical security tests, but it’s something I think about often. The more I learn about Internet infrastructure, the more I realize how centralized and concentrated it truly is. A small number of Tier 1 ISPs carry the majority of global traffic, excluding direct peering or IXPs (Internet Exchange Points). If you spend time looking at global fiber maps—whether within the U.S. or internationally—you’ll quickly see a few strategic choke-points where, with the right access, you could observe massive volumes of traffic just by tapping into a handful of links.

At the application layer, the situation isn’t much different. A large portion of Internet-facing infrastructure is concentrated in a few major players: AWS, GCP, Azure, Cloudflare, Akamai, and so on. If you dig into TOR relays, you’ll notice many are hosted with common cloud providers like OVH, Hetzner, DigitalOcean, and AWS. Even though TOR is decentralized in theory, in practice there’s still a lot of provider overlap—and some relays are run by anonymous volunteers without much accountability.

I wouldn’t place a huge amount of trust in VPNs or even TOR when dealing with a well-resourced adversary, like a nation-state. Even if your VPN provider runs memory-only servers, has undergone independent audits, and maintains a strict no-logs policy, that doesn’t stop upstream or downstream observers from conducting traffic correlation. Over a long enough timeline, those kinds of passive observations can reveal a lot—especially when the adversary has access to backbone traffic.

This isn’t even getting into active attacks like BGP hijacking, which has been used in the past to deanonymize TOR users (see also RAPTOR: Routing Attacks on Privacy in Tor). Combine a few malicious relays with nation-state-level network visibility, and it’s hard not to imagine targeted de-anonymization being a solvable problem with enough patience and positioning.

I’m not trying to make sweeping claims here, just sharing a perspective. The more you understand about Internet routing and global infrastructure, the more skepticism you develop toward the idea that tools like TOR or VPNs can guarantee anonymity against sophisticated actors. For casual use, they offer value. But against a determined, global adversary? It’s probably not enough.

I’m fortunate enough to not have to be in these types of positions, and hope that I never am, but if I had to I wouldn’t personally be comfortable betting say my life or freedom that these services would be capable of protecting me from a dedicated well-resourced adversary after seeing what can be done with published research on relatively small budgets.

A Quick Disclaimer

I’m by no means an expert on Internet routing or BGP and so if I get something please feel free to reach out to me on LinkedIn or through another channel and I can update and make corrections to the article. To be honest, I didn’t want to wait to publish this article until I perfectly understood everything as this is an ongoing learning process as I research different aspects of what I’ve observed in this article. I’d rather publish something quickly and share my observations versus wait a long-time and potentially never finish or publish the article.

This is just a quick article I wrote up over a weekend in order to share some of my observations with others. It’s not meant to be a fully comprehensive guide. I’m still in the process of learning about this stuff and how various aspects of Internet function, etc. I just wanted to share some neat observations I made during my research into web conferencing traffic tunneling.

Conclusion

It’s easy to think about internet speed as just a number—500 Mbps, 1 Gbps, whatever your ISP promises. But in practice, where your packets go matters just as much as how fast they can travel. Routing isn’t just a network engineering concern it’s a key consideration that red team operators should keep in mind when performing testing especially in regard to traffic tunneling or rapid data exfiltration.

The last mile used to be the problem. Now, in a world of cheap and abundant fiber infrastructure the real bottlenecks are often upstream and driven by various incentives such as geopolitics, disagreements profit-driven private sector actors, cost optimization, and other factors.

I hope this article provided you some useful context you could potentially use on red team engagements or even when designing applications or services for geographically distributed users (it’s kind of the same thing at the end of the day). If you are curious about tunneling traffic through web conferencing infrastructure definitely check out my talks at Black Hat and DEF CON alongside the blog post series I released on the Praetorian blog titled Ghost Calls: Abusing Web Conferencing for Covert Command & Control (part 1, part 2).